(Update 2023-03: I wrote this in 2020 when GPT-3 was highly hyped, but ultimately made only <1% of the splash that the monstrous ChatGPT made 3 years later. If I had to rewrite this today, I’d 1) think more kindly about defensibility, especially through deep product, user experience, and marketing/distribution (see Elad Gil article); 2) be more pessimistic about how much value foundation models can capture, given open-source competitors and possibly declining returns to increasing scale. But the rest of it seems to have held up well, especially around how easily incumbents can integrate LLM’s into their products and thus smother new entrants.)

GPT-3 is an amazing technology. Within a few weeks after beta API access opened, a host of jaw-dropping demos popped up, from automatic code generation to automated therapy bots to writing original poetry and Navy SEAL copypasta memes. It does things that would have been science fiction 10 years ago. GPT-3 and its successor algorithms are going to change entire industries.

Naturally, tech founders and VC investors are salivating at the possibilities of turning GPT-3 applications into businesses.

But a good technology doesn’t necessarily make for a good business. The fact that GPT-3 works so well out of the box should be terrifying to founders. Here’s why:

- If it’s easy to make a good-enough app out of the box, the barriers to entry are mercilessly low. Dozens of competitors for your idea will spring up literally overnight, as they already have in these Twitter demos.

- It’s not just about new entrants. If GPT-3 is so easy to adopt and build products with, incumbents will do it too. Thus, in Clayton Christensen’s framework, GPT-3 looks more like a sustaining innovation than a disruptive innovation. This will strengthen existing winners more than it creates openings for new startups.

- If the baseline GPT-3 performance cannot be substantially improved to create a substantial (10x) proprietary edge, the competition will shift away from technology to other dimensions of competition—particularly in marketing and distribution. This is where incumbents beat startups.

- Meanwhile, the profits will accrue to the true beneficiaries: 1) the foundational model owners, OpenAI (and, by extension, Azure), 2) to marketing platforms, particularly Google and Facebook, 3) to the true shovel sellers, the chip manufacturers like Nvidia and TSMC. All have tremendous pricing power and can raise pricing to the point where companies built on each are barely profitable.

Let’s dive more into these ideas.

Low Barrier to Entry = Fierce Competition

Moats provide an enduring competitive advantage. The wider and deeper the moat, the higher the barrier to entry to compete with your business, and the less capably a hotshot teenager can start a new company to compete.

If a moat is shallow, hundreds of competitors can pop up overnight and provide a good-enough competing product. If you can’t build a meaningful product advantage, then the grounds of competition shift to other dimensions of competition—namely, marketing and distribution.

The Parable of Online Mattresses

The online mattress industry had shallow moats and played out predictably. A few years ago, if you wanted to start a new mattress company, you only needed to cobble together a few components:

- A manufacturer

- A website

- A marketing campaign

At the peak of the industry, there were 175 online mattress companies. None had a meaningful product advantage—many used the same mattress manufacturers. (And having personally tried several of these mattresses in stores, they really did feel about the same.)

The grounds of competition thus shifted to marketing and branding, which is why a year ago you heard so many podcast ads for Casper, Purple, and the like. When product 17 and product 130 are identical, then the only way to win is to get buyers more familiar with product 17. But when competition meets a narrow dimension of competition, profits evaporate—companies bid up marketing prices to the highest that they can endure. It became a game of chicken—how much are you willing to spend to acquire a customer? The best-funded startups “won” this branding battle.

But this was a short-lived victory. The ultimate result: perpetually unprofitable businesses, with companies spending most of their revenue on COGS and user acquisition. Casper now has a market value of just $350 million, down from its peak private valuation of $1.1 billion.

Meanwhile, the real beneficiaries of all this funding are:

1) the companies selling shovels in the gold rush, including mattress manufacturers and marketing platforms (particularly Google and Facebook)

2) customers, who enjoyed rock-bottom mattress prices subsidized by venture capital.

This situation played out in meal kit companies too, and one could argue the same is true of Uber vs Lyft and the food delivery war going on now.

Can You Differentiate Yourself with GPT-3?

Because GPT-3 works so well out of the box, I see this playing out a similar way. To start a new AI company, you need only cobble together a few components:

- A product built on GPT-3’s (very easy to use) API

- A website

- A marketing campaign

As we see with Twitter demos, the products you can make off the shelf will frankly be pretty good.

Unfortunately, most of the products built on GPT-3 will be identical to each other, and few will have a meaningful edge. We’ll dive more into this next.

Differentiated Technology

To win a market primarily through technology, your product needs to be obviously better to the user. When Google first came out, it delivered such better search results than other engines—possibly by a subjective factor of 10 or more—that there was little reason to use any competitor. When Dropbox first came out, its syncing and ease of use was unbeatable. Right now SpaceX has a rocket that can do what no other company’s can, at an unbeatable price. These companies have real technology moats.

In contrast, if an industry has products that are are more or less identical—like online mattresses—the grounds of competition shift elsewhere other than product (like marketing and distribution), and there is no technology moat.

So imagine: If 100 companies build an AI therapy bot with GPT-3, how different will their user experiences be? How far ahead will company #1 be above company #2, and then over company #10? Will there be a 10x difference? Or more like a 5% difference?

I argue: The better GPT-3 works out of the box, the harder it will be for any single company to build meaningful differentiation. Frankly, early demos already look very good.

Imagine how much better it can get with just a little more work—a modicum of fine tuning on therapy conversations and user safeguards. This is the new baseline, the “table stakes” for any new entrant, which is going to be relatively easy to achieve.

And then from this baseline, how much better could any one company get?

Here’s one way to think about it. The pinnacle of AI therapy would be a bot that rivals the best human therapist. Call this the 100% experience. The average human therapist might be somewhere at the 85% bar. And then a human user might be willing to tolerate a “good enough” AI performing at 70%—it’s clearly worse than a human therapist, but usable enough that it can keep up a coherent conversation and remembers that you were bullied in 5th grade.

Before GPT-3, building anything close to the Good Enough AI was really hard. A company would have needed to invest many millions into its own algorithms and data cleanup to get anywhere close to the human user bar.

In this environment, the leading company had a few advantages:

- The barrier to entry was high, so it faced less competition.

- The spread between the #1 and #3 companies was high, meaning the leading company had a sizable moat.

- It still had a lot of room to grow to get to 85%+ level—this is room in which it could carve out a meaningful edge over competition.

- It owned its own technology, so it could iterate to continuously improve its experience.

Here’s how the landscape might have looked:

(In practice, I don’t know of any pre-GPT-3 AI therapy bot that comes anywhere close to a human therapist. So competitive lead notwithstanding, I don’t think there have been any good AI therapy businesses to date.)

Then comes GPT-3. Now anyone can produce a “good enough AI therapy bot,” with a modicum of fine-tuning and UX design. This outcome wouldn’t be shocking—people were producing plausible demos within days of accessing the private beta. Imagine what can be done with just a few weeks of work and $500,000 of investment.

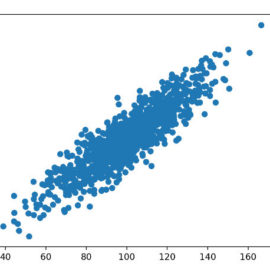

The result: the range of competition narrows:

Compared to the previous situation:

- There are many more competitors who can offer a “good enough” product.

- The range of competition is compressed into a narrower band. It becomes much harder for any single product to stand out from the median product, which is already quite good.

- Because the companies don’t own the core technology behind GPT-3, their ability to improve beyond the baseline performance is limited. Yes, they can fine-tune GPT-3 with their proprietary data, but how much is this going to improve on the core algorithm, which cost $12 million to train on 40GB of Internet text? And won’t everyone else be fine-tuning like this too?

Again, this really gives credit to OpenAI for how well GPT-3 works—out of the gate, you can produce a pretty usable product. But for startups, this merely raises the table stakes instead of offering a competitive advantage, and it neutralizes the technology edge any single company can have over another. Great for OpenAI, not great for new startups.

Then imagine how much worse this will get when GPT-4 comes out. And again with GPT-5. The minimum bar of quality will keep inching up inexorably, and the range of competition will be compressed further and further.

Plus, it’s likely that any proprietary progress you make on GPT-3 will be totally wiped out by GPT-4; the same way your tweaks on GPT-2 would have been wiped out by GPT-3.

We’ve talked about AI therapy here, but this argument extends easily to automated code generation, creative writing tools, chatbots, Q&A services, games, and so on.

Other Avenues of Differentiation

Yes, the algorithm isn’t everything. Products can still differentiate with their user experience, product design, customer support, adding on human services, and so on.

But as far as tech companies typically go, this is not the hard part of building a company. It’s a relatively shallow basis for competition, and lots of capable product builders can do it. And eventually you look more like a service company than an AI software company.

SpaceX is an exclusive leader now, but imagine if new companies SpaceY and SpaceZ came out with equivalent reusable rockets with identical cost performance and reliability. What are they going to compete on—the padding of the seats in the Dragon capsule?

To wit, robo advisors like Betterment, Wealthfront, and Charles Schwab all have more or less the same algorithms. They all make you the same amount of money the same way. What would make you choose one over any other? How much do you care about that difference?

Key Questions to Watch

Admittedly, it’s still early days, and it’s unclear exactly how far a company can improve on GPT-3’s baseline. The key questions to watch here:

- How much can a GPT-3 user improve on the base algorithm experience in a proprietary way? Can you get 5% better than stock performance? 50%? 1000% better?

- What does the improvement curve look like, as a function of effort and investment? How quickly do diminishing marginal returns diminish? How quickly does the improvement plateau?

- To get to the sweet spot of that improvement curve (80-20 rule), how much investment do you need to make? Is it something that costs $100 million, or something that an unfunded group of passionate Stanford students can do?

My predictions are pessimistic:

- That GPT-3 represents the lion’s share of the user experience, and any improvement beyond that is mostly window dressing

- That because GPT-3 already constitutes such a large dataset and heavy training, marginal improvements are hard to come by and will look log-linear

- That any proprietary improvements made in the near future will be rapidly eclipsed by GPT-4 and competing algorithms (eg from Google, AWS, Salesforce)

- That a very well-funded startup will only have a slightly better technology than a bootstrapped one.

But I’d love for any AI experts to tell me how wrong this is.

Are Other Moats Possible with GPT-3?

Differentiated technology is just one of several classic moats. Are other moats possible with a company built around GPT-3? Let’s examine the other possibilities: Economies of Scale, Network Effects, High Switching Costs, and Branding.

Economies of Scale

If your company get bigger, does your product get cheaper? For Amazon, the answer is yes: its fixed investments in infrastructure are spread across many more orders; it exerts pricing power on its suppliers; its advertising scales across many more users. If Amazon can secure more users, it becomes more profitable.

For Spotify, the answer is not really. Every time a user plays a song, Spotify pays a royalty to the song owner. Thus, as revenues grow, the cost of revenue grows as well. If Spotify is currently losing money per user, adding a million users causes it to lose more money.

(Source: Stratechery)

For music, Spotify doesn’t have a choice—people want to listen to The Beatles and Taylor Swift, and shedding these artists would cripple the listening experience. (This is why Spotify is investing so heavily in proprietary content, particularly in podcasts, like paying $100 million to get exclusive with Joe Rogan. For Spotify, owning proprietary content weakens its reliance on the recording industry and improves its unit economics.)

How about companies built on GPT-3? While the beta API is free, OpenAI will charge for API access. Every API call will cost you money. As you get more users and users use your product more, you will pay OpenAI more money. This sounds more like a Spotify situation than an Amazon situation.

The root cause: you don’t own GPT-3, you’re merely renting it, just like every other company.

And if your product depends on GPT-3 with no viable alternative, just like Spotify is reliant on record labels, you lose all the pricing leverage.

(While for now OpenAI has an apparent monopoly on models that work as well as GPT-3, I expect AWS and Google to offer competing services soon, given that GPT-3 seems to be less about a novel architecture and more about scale. To Amazon and Google, $16 million to train a model is peanuts.)

Other Moats

Economies of scale and differentiated technology are typically the most relevant moats for AI companies. Let’s go through the others:

Network effects: the more users who use it, the more valuable the service gets.

The simplistic reflex answer here is that AI companies can achieve this with data, but whether this effect even exists in AI is questionable. If the marginal improvements to more data plateau quickly, then companies with more data won’t have an advantage.

Otherwise, GPT-3 doesn’t seem to have inherent network effects—you can still build viral services with GPT-3 added on (say, social networks augmented by AI chat), but GPT-3 doesn’t intrinsically enable this moat. In fact, since the most obvious uses of GPT-3 are human-to-computer interactions, it might be anti-network building.

High switching costs: the harder it is move off a service, the better you retain your customers.

Let’s take AI therapy bots again. Theoretically, the more you interact with the bot, the more memory it has of past conversations, and the more relevant future conversations will be. This is, after all, why people keep their good human therapists—after you spend 20 hours with someone, they understand your life story and come up with better insights. It’s a pain to switch to a new therapist, to whom you have to repeat your life story.

But with GPT-3, it’s likely this effect quickly taper off, particularly because GPT-3 only has a limited “working memory” (currently limited to around 1000 words). If you watch someone play AI Dungeon for a few minutes, this becomes apparent—while it stays fairly coherent in a narrow time window, it forgets characters and events that came just 5 minutes earlier.

So if an AI therapy bot works as well after 20 minutes of interaction as it does after 20 hours, switching costs to the next AI therapy bot are low.

Branding: GPT-3 doesn’t really enable brand loyalty other than contributing to the quality of your product. But this is something that every GPT-3 user has access to.

Traditional Business Moats

So far I haven’t talked about traditional non-tech moats, like user experience, deep featureset, marketing/branding, sales relationships, sticky engagement, partnerships, regulation, and so on. I won’t discuss them here because they apply to any industry using any technology, and they aren’t specific to GPT-3. Here I’m more concerned about whether GPT-3 itself confers a durable advantage to a business that uses it, and I assert it’s much less than what early adopter companies are thinking.

Of course, between two GPT-3 chatbot companies with equally good products, the one with better marketing and sales is going to beat the other. And don’t get me wrong, you can still build a valuable ($100 million+) company just on superior user experience, marketing/sales, and other traditional execution stuff, without having any magical underlying technology – just look at Intuit, Atlassian, or Hubspot. But this was always true before GPT-3 and will continue being true, so it’s not an interesting point to go into.

Market Incumbents Benefit from GPT-3

The title of this post is “Starting a Business around GPT-3 is a Bad Idea.”

But established, successful incumbents are really going to benefit from technologies like GPT-3. In Clayton Christensen’s terms, GPT-3 becomes a sustaining innovation that benefits the existing players, rather than a disruptive innovation that benefits new entrants.

Primer on Sustaining vs Disruptive Innovations

Read The Innovator’s Dilemma for more details, but here’s a summary:

Sustaining innovations offer better performance or cost savings to existing products. They most benefit market leaders, who use sustaining innovations to augment their existing products. Thus, sustaining innovations serve existing markets rather than creating new markets. They fit easily within the incumbents’ value chain and don’t require a massive reorganization of the organization to adopt.

- Within pharma, new biological discoveries showing new drug targets benefits existing giants like Pfizer who have the infrastructure to pursue those leads.

- For Internet companies, the switch from on-site server hosting in the 1990s to cloud servers benefited existing incumbents, who used cloud hosting to lower their operational costs.

Disruptive innovations offer significantly worse performance than existing products; they at first look like toys, nothing that any professional user would rely on. They’re thus ignored by most of the market, which requires higher performance, except for a passionate niche of hobbyists. In turn, they’re ignored by incumbents, who see the hobbyist market size as too small; and often the disruptive technology would cannibalize the incumbent’s business model. Therefore, the only people working on disruptive innovations are upstarts. Over time, the disruptive technology improves rapidly until it catches up to the incumbent technologies, and soon overtakes it.

- The personal computer disrupted the mainframe computing industry. At first, the PC wasn’t powerful enough for corporate use. Meanwhile, mainframe leader IBM couldn’t switch over to PC’s easily, since it would cannibalize their high-cost mainframe sales. Over time, the PC became more than powerful enough for professional use, and it swallowed the mainframe market.

A tricky but important point: the same innovation can be disruptive to incumbents in certain industries, and sustaining to incumbents in other industries. While the Internet disrupted entire industries like publishing, it was sustaining to the computer manufacturer Dell, whose direct-business model fit the Internet perfectly. Having been founded in 1984 and already an established incumbent well before the Internet became popular, Dell really took off in 1996 when it started taking sales through the Internet.

Says Clayton Christensen: “Is the innovation disruptive to all of the significant incumbent firms in the industry? If it appears to be sustaining to one or more significant players in the industry, then the odds will be stacked in that firm’s favor, and the entrant is unlikely to win.”

GPT-3 Benefits Incumbents

So where does GPT-3 fit in?

On the one hand, GPT-3 clearly disrupts the most traditional players in the industry. AI therapy bots disrupt the classic human therapists, who charge a lot of money for human time and a nice office. AI legal research services disrupt lawyers and paralegals, who spend a lot of time scouring legal history for relevant cases. This is how most excited founders are thinking.

But this analysis is incomplete. It ignores the many powerful incumbents equipped to make use of GPT-3 as a sustaining innovation—particularly companies that already deliver services through the Internet and are itching to produce a better product at a lower cost.

Incumbents can easily use GPT-3 because it works right out of the box. Capital expenses are low, and building a GPT-3-powered product wouldn’t require a drastic overhaul of the company’s business model.

Thus, I can easily see existing incumbents in each industry adopting GPT-3 to augment their existing products and extend their lead:

- Headspace, Calm, and Talkspace will build AI mental health bots

- One Medical, Teladoc, and GoodRX will build AI healthcare bots

- Khan Academy and Chegg will build AI tutors

- Google Docs/Gmail, Microsoft Office, and Grammarly will build AI email/document composers

- WeightWatchers, MyFitnessPal, and Noom will build AI weightloss coaches

- Peloton, Lululemon, and Strava will build AI fitness coaches

- LexisNexis and Westlaw will build AI legal research services

- Bloomberg and New York Times will build AI-generated content

None of these sound far-fetched. These companies are all technology competent. Developing good products would cost little in capex (again, given how well GPT-3 works out of the box). And such products already fit will within their value chains.

Combined with our first section: the incumbents will build equivalently good products as startups (probably better ones), and they will win with their sheer force of branding, distribution, and user loyalty.

If you’re building a new AI therapy bot, can you reasonably compete with Talkspace, the mindshare leader in online therapy? If you’re building a new AI email writer, can you compete with Grammarly, which already has 20 million users?

New Markets Without Incumbents

Don’t get me wrong, there will be some pockets of opportunity, especially in industries without innovative incumbents and in entirely new markets. Some of the most imaginative uses of algorithms like GPT-3 have yet to be discovered, the same way early users of the Internet in the 1990s didn’t foresee Airbnb and the blockchain.

In these new markets, the earlier commentary still applies—competition will be fierce, especially if it takes little time to spin up a clone once the new business model is proven. Companies will need to build up a competitive edge another way.

Finally, building a successful company obviously isn’t everything. There will be plenty of useful free tools that help creative writers spawn ideas, let lonely people talk to something, figure out their homework, and so on.

In Summary

GPT-3 really can do amazing things, and I can’t wait to see what GPT-4 and competing offerings will do. As a consumer, this signals an incoming wave of AI-powered interactive experiences that would have sounded like science fiction 10 years ago.

But for a company founder, GPT-3 seems like a shaky foundation to build a new company on.

- The barrier to entry to developing a viable product gets low for everyone, meaning hundreds of competitors will pop up overnight.

- At the same time, how high you can build a proprietary competitive advantage is unknown. Given how black-box and closed GPT-3 is, I suspect it’ll be low.

- Any technological improvement you make in the near future might be wiped out by the huge advancements of GPT-4 and likely soon-to-come competing algorithms (say, from AWS or Google).

- All this pushes the dimensions of competition off of technology and toward marketing, branding, and distribution. This is where incumbents have a massive advantage. (Also, it’s where product/tech-focused founders don’t like to compete.)

A lot of founders are going to try to start businesses based on GPT-3, and a lot of money will go into them, and it’s going to be a blood bath.

The best companies to start around GPT-3 will be in industries where no incumbents can credibly make use of the technology, and where a product can achieve meaningful differentiation to get a long-term advantage.