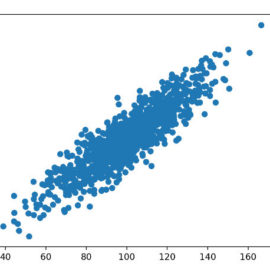

The Early Childhood Longitudinal Study (ECLS), launched by the US. Department of Education in the 1990s, measured the academic progress of over 20,000 students as they progressed from kindergarten to the fifth grade, interviewing parents and educators and asking a broad range of questions about the children’s home environment. The study provided an ample resource of data that researchers could use to identify more statistically meaningful relationships between specific parenting tactics and children’s academic outcomes.

Researchers used regression analysis to draw conclusions from this rich data set. Regression analysis enables researchers to isolate two variables in a complicated and messy set of data, holding everything else constant to identify relationships between variables. Its main benefit is that it allows analysts to control for confounding variables that might otherwise confuse the true causal relationship.

It is important to note that regression analysis does not “prove” causal relationships. The only way to truly do that would be to set up a randomized, controlled experiment, similar to what would be done in a clinical trial for a new pharmaceutical. This is very hard (if not impossible) to do in a field like economics, where it is highly impractical to create these conditions. Thus, economists use regression analysis to study causative relationships in natural experiments.

According to the ECLS study, these are the factors that were strongly correlated with children’s test scores:

- Having highly educated parents

- Having parents with a high socioeconomic status

- Having a mother thirty or older at the time of her first child’s birth

- Being born with a low birthweight

- Speaking English in the home

- Being adopted

- Having parents active in PTA

- Living in a home with many books

Meanwhile, these factors were not correlated with children’s test scores:

- Coming from a traditional, two-parent home

- Moving to a better neighborhood

- Having a stay-at-home mom between birth and kindergarten

- Attending Head Start

- Regularly attending museums

- Being spanked on a regular basis

- Watching television frequently

- Being read to daily

If you look at the lists of factors above, do you notice a pattern? Most of the traits that correlated with academic performance were immutable characteristics that parents possessed. They were either rooted in the parents’ identity or had to do with things the parents had achieved before they had children. They weren’t active decisions made by the parents.

Accordingly, the traits that weren’t linked to children’s academic performance were things that parents made the deliberate choice to do (like going to museums, reading, limiting TV).

In some ways, this is unsatisfying. We like to focus on what tangible things we can do (like reading to our kids or cutting their TV time), and we like to believe those actions make a difference. In contrast, we don’t like being subject to environmental causes outside our control (like how rich our parents were), because it punctures the idea that we as individuals are fully in control of our own destiny.

But regardless of how we feel, the data speak for itself. Who parents are, what attributes they possess, matters more than what they do. Parenting may not make a difference—but parents most likely do.